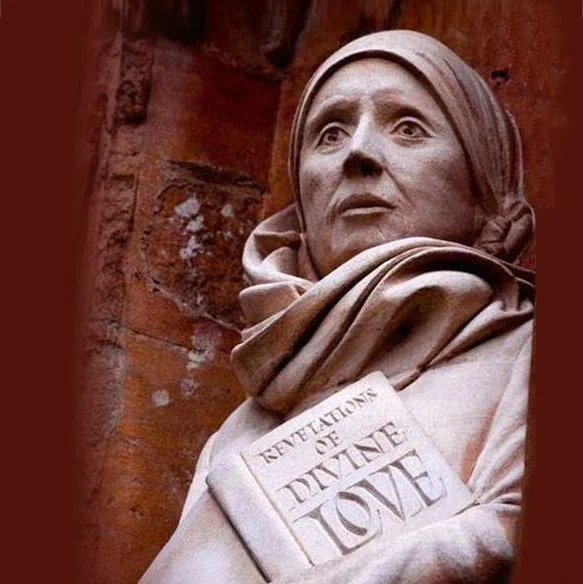

A sculpture of Mother Julian at Norwich Cathedral.

The great English mystic Julian of Norwich (1342-1418) lived at a time of pandemic and war, a time of enormous suffering and anxiety similar to our own, yet she received a profound vision of God in which she saw that “Love was his meaning”, “all shall be well”, and “Peace and love are always in us, living and working”. The Rev’d Philip Carter* pays tribute to a remarkable woman and her book Revelations of Divine Love, which was the first to be written in English by a woman.

There is no doubt that Julian is one of the greatest of the English mystics, and not only that, but one of the greatest English theologians too. For Thomas Merton, Julian is a “true theologian”, “one whose prayer is true”, and in whom there is no split between theology and spirituality. In her writing she demonstrates the end of a long cleavage between head and heart, theology and spirituality, what is called a “dissociation of sensibility”.

For Julian sees God as the ground of all reality: for her God is both intimate and knowable. As a theologian she is not abstract, speculative or systematic, but highly imaginative. She does not simply rest or rely on received doctrine: she brings to her lived experience “kindly reason”, and constantly probes and questions the received doctrine of her Mother Church. Everything she says about God is grounded in the everyday realities of life. For Julian, God is as God does.

Thomas Merton calls her a wise heart, a true theologian with clarity, depth and order. He says of her theological method that “She really elaborates, theologically, the content of her revelations. She first experienced, then thought, and the thoughtful deepening of experience worked it back into her life deeper and deeper”.

Her theology is marked by a profound simplicity and an invincible hope. Merton says that “One of her most telling convictions is her orientation to what one might call an eschatological secret, the hidden dynamism which is at work already and by which ‘all manner of thing shall be well’. This ‘secret’, this act which the Lord keeps hidden, is really the fruit of the Parousia. It is not just that He comes, but He comes with this secret to reveal, He comes with this final answer to all the world’s anguish, this answer which is already decided, but which we cannot discover until it is revealed”.

I begin deliberately with Julian’s theological method and her theology of the Last Things, as it undergirds in highly dramatic form almost her entire understanding of the centrality of Love as God’s meaning, her faith, or as she would say, her “sure trust” in that Love, and the invincible hope that permeates her vision of God and God’s relationship with all that is. In the bloodied face of the Crucified she sees nothing less than the community of love, the Trinity: our future who has already appeared and the end towards which everything moves.

Julian’s vision is of a God who is a relational network of love and loving which connects all of creation and humanity: a God of self-giving love, pouring God’s self out towards one another in the community of Love (Trinity), and loving us as if we were God.

Julian is utterly realistic: this world is full of “well-being and woe”. And because of this realism, and her willingness to ask the hard questions, she offers us a unique insight, which is the heart of her theology: “not solving the contradiction, but remaining in the midst of it, in peace, knowing that it is fully solved, but that the solution is secret, and will never be guessed until it is revealed.”

This is a remarkable vision, given the context of fourteenth century England in which she lived, a context which in so many ways resembles ours. During her lifetime there was much social, political and theological turmoil and change. It was the time of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), the Black Death, which struck the commercial port of Norwich so severely that between a third to two thirds of the population died during the three occasions the Plague struck.

The Pope had been in exile in Avignon since 1309 and the Great Schism occurred in 1378, with three contenders quarrelling over the Papacy. Religious Orders were often at loggerheads with each other: there was growing criticism by Wyclif and the Lollards of the Church’s corruption and confusion. (Not far from Julian’s cell was the fire pit where dissenting Lollards were burned.) It was also a time for fellow mystics, and alongside Julian, there are the writings of Richard Rolle, Margery Kempe, Walter Hilton, and The Cloud of Unknowing.

While Julian does not explicitly mention the details of the social and political and ecclesiastical milieu and context in which she lived, her dominant and profound emphasis on hope - her constant refrain that “All shall be well” - is surely the remarkable fruit of living with both “sure trust” and “true understanding” in such an environment.

Because of this, across a span of over 600 years, Julian speaks with both passion and conviction into our world. In many ways, with the anxiety over climate change, the decline of institutional religion and in belonging, which could be characterised by dis-connection and fragmentation, our own experience of a deadly pandemic, the threat of nuclear disaster, the endless wars that threaten peace and stability in the Middle East and Ukraine - to name just a few - all seem to mirror quite precisely the world of Julian.

On May 8th, 1373, on the point of death, her pain suddenly left her and a series of wonderful “showings” (as she calls them) began. These revelations of God’s love centred on the Cross of Jesus - her heaven. She recovered and wrote of them in what is known now as the Short Text. She reflected on them for 20 years, and then wrote what is known as the Long Text – reflections of profound depth and wisdom, exploring the meaning of such revelations. She has been described as “the mother of English prose” for her Revelations of Divine Love is the first book written in English by a woman.

Julian wrote not just with passion but compassion. She probably wasn’t a Benedictine nun: she may have been married, with children. She claimed to be “unlettered”. She wrote for her “fellow Christians”: “In all this I was greatly moved with charity towards my fellow Christians. I wished they might see and know what I was seeing, as a comfort to them. For this whole vision was shown to all in general” (LT8).

After her Showings she became an Anchoress (anchor meaning to retire, though we might better understand her commitment as an “anchored presence”). She lived in a cell attached to the church of St Julian (from which she probably took her name), and her cell had three windows: one opening up to the Sanctuary of the church, where she could hear Mass and receive Communion: one window where a servant maid could bring provisions for her; and one window where people could come for spiritual counsel.

Julian is a realist when it comes to the human condition. She is certainly no sentimentalist. For her, there is “no harder hell than sin”. Yet she can also say sin is “no-thing”. Sin has no substance, no being. We know sin however by its effects, by its pain and suffering. Because of this she can believe in hell, but she is just as clear that the wrath or anger we experience is not God’s. Yet such pain is only for a time - for it “purges us and makes us know ourselves and ask for mercy” (LT27).

In God, she sees, there is no anger. “Between God and our soul there is neither wrath nor forgiveness in His sight”. God cannot forgive, because there has never been a time when God has been unforgiving. “God tenderly preserves us while we are in sin ... He touches us most secretly, showing us our sin by the sweet light of mercy and grace” (LT40).

But God “did not say: ‘You will not be troubled’ or ‘You will not have bitter labour’ or ‘You will have no discomfort’, but ‘You will not be overcome’. God wills that we pay attention to this truth and that we be ever strong in faithful trust, in well-being and woe” (LT68).

According to Julian our life is a “marvellous mixture of well-being and woe” (LT52). Julian considers that our ignorance of love keeps us in despair: she offers us a radical vision of created reality, where she doesn’t deny the reality of sin but, because our vison is distorted, she wants us to see things as God sees. So she can say: “Peace and love are always in us, living and working, but we are not always in peace and love” (LT39).

For Julian it is always a case of both/and, not either/or. So she can say: “In God’s sight we do not fall: in our own sight we do not stand. And both of these are true, as I see it. But the way God sees is the higher truth” (LT82). So “Peace and love are always in us, living and working” is the higher or absolute truth: this is the way God sees. “We are not always in peace and love” is the lower or relative truth: the way we see. And she would counsel us by saying: Don’t ever deny the lower truth, but NEVER, NEVER deny the higher truth.

So she was always captivated by the higher truth about our relationship with God. It was not that she did not appreciate or value her humanity, nor the circumstances of her every-day. But as a profound theologian it was always the higher truth of God, God’s activity, God’s goodness, God’s grace which captivated and empowered her.

Julian was profoundly conscious of an inner depth within her. This “hidden person of the heart” - this “anchored presence” - was the indestructible secret of her life, the calm of the ocean’s depths below the surface “storms” of sorrow and woe. Christ, she saw, was in this deep “inner part” (our “substance”), and he can reach and inform our “outer part” (our “sensuality”). Sin has fractured the unity between our substantial nature (who God sees), and our sensuality (the way we see ourselves). But “in our merciful Mother we are made and restored. Our fragmented lives are knit together and made perfect ... And by giving and yielding ourselves, through grace, to the Holy Spirit, we are made whole” (LT58).

Prayer for Julian was both a gift and natural. She did not necessarily subscribe to the popular idea of a “ladder” of prayer, a steady progression upwards. For her, life as it is lived is simply falling down and rising again. Rather than struggling with ideas about prayer, it is who we are that matters: prayer is simply the living and lived expression of who we are. So we need both “true understanding” of prayer, and a “sure trust” (LT42).

The fruit and end of prayer is at-one-ment: “oned and like God in everything”. “By nature our will wants God, and the good will of God wants us”. For “By his grace our Lord aims to make us like himself in heart as we are already in our human nature”. Prayer for Julian is certainly asking, or beseeching: but it is not self-generated: “He moves us to pray for what he wants to do”. For Julian: “The best prayer is to rest in the goodness of God and to let that goodness reach right down to our lowest depth of need” (LT6).

In the early part of her Showings Julian offers us a memorable image: the image of the hazelnut. This little thing, in the palm of her hand “is all that is made”. She was shown that “It lasts and ever shall because God loves it”. “In this little thing I saw three truths. The first is that God made it. The second is that God loves it. The third is that God looked after it” (LT5). God is indeed our maker, our lover and our keeper.

Remarkably, in the past few decades, we have been captivated by those first extraordinary photographs from space of the earth, “a tiny thing as small as a nut and yet the ground of all humanity”. As one astronaut has written of this image of the earth, “so small and so fragile that you can block it out with your thumb ... and [you realise it] is everything that means anything to you - all of history and music and poetry and art and death and birth and love, tears, joy, games, all of it on that little spot…”

Thoroughly grounded in the realities of our everyday life, connected with everything that is in our common humanity and the entire cosmos, Julian’s great gift, through the passion of the bloodied face of the crucified Jesus, is that she sees nothing but compassion, at the heart of the community of love we call the Trinity, and at the very heart of everything that is made. No wonder she could say that Love is God’s meaning and live out, in her own life, the truth that Love is our meaning as well.

Philip is a retired Anglican priest. His ministry included founding the Julian Centre (1997-2009), an independent and ecumenical spirituality centre in Adelaide, South Australia. He was also the inaugural president of the Australian Ecumenical Council for Spiritual Direction from 2006 to 2009.