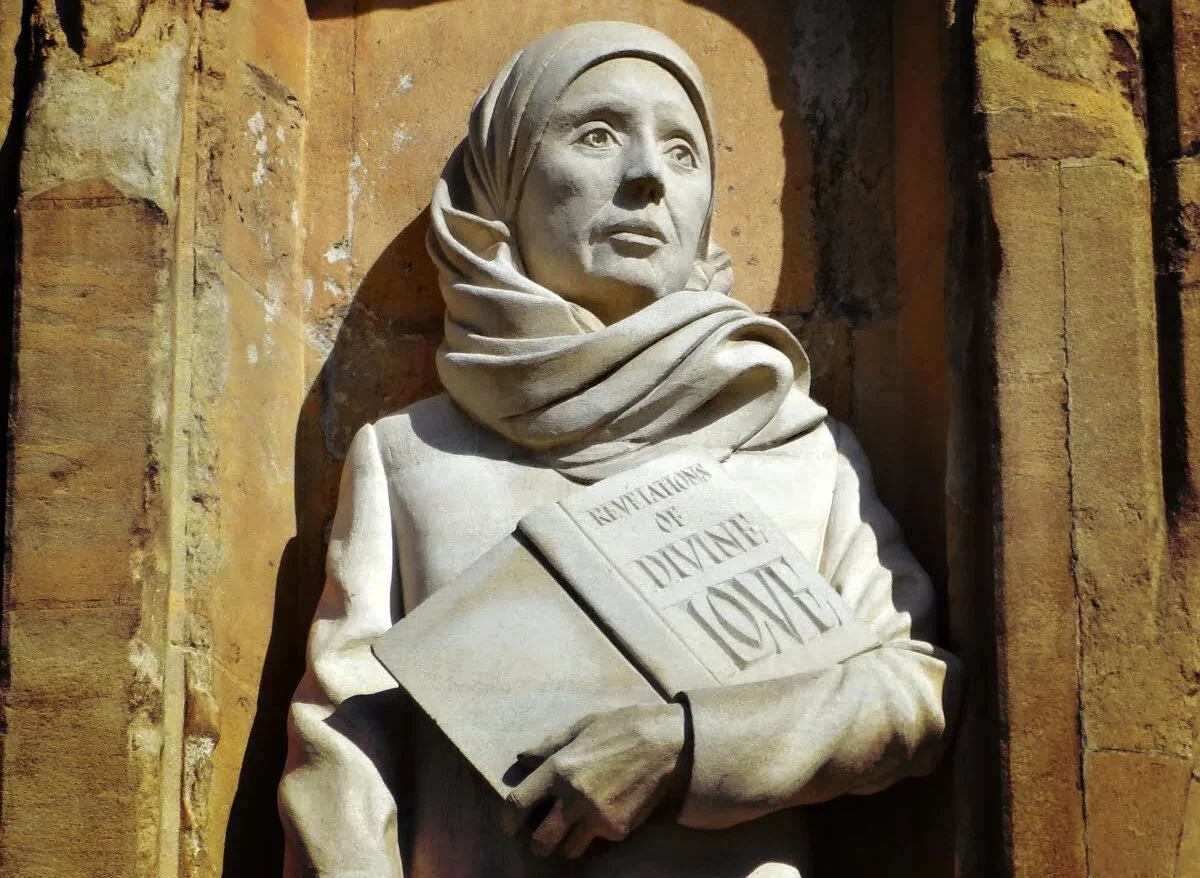

A sculpture of Julian of Norwich at Norwich Cathedral.

14th century mystic Julian of Norwich lived in the midst of great suffering, but her vision and experience of the crucified Christ gave her profound insight into the human condition, and our lives of “well-being and woe”. Author and spiritual director Philip Carter reflects on Julian’s message of hope for humanity that “all will be well” because love will overcome.

One of the first things that has always struck me about Julian of Norwich is the context in which she lived. During her lifetime – she lived in the 14th century - there was much social, political and theological change. It was the time of the Hundred Years War (1337-1453), the Black Death (the first Plague in the years 1348-49), the Pope had been in exile in Avignon since 1309, and the Great Schism occurred in 1378 with three contenders quarrelling over the Papacy. Not half a mile away from her cell, Lollards and heretics were being burned alive. It was a time of immense moral and doctrinal corruption - yet it was also the time of Chaucer (The Canterbury Tales), a fruitful time for mystics, including Richard Rolle, Margery Kempe, Walter Hilton and the author of The Cloud of Unknowing.

It is a good reminder - each time I have my quiet time in the morning - to remember the context of my life: the personal and relational context of family and friends, as well as the wider context of social, national and international events. This calls out from me the need to be as open as I possibly can: to listen to my responses, reactions and feelings about circumstances and events over which I have no control.

For a good part of her life she lived as an Anchoress, in a cell, attached to St. Julian’s Church in Norwich, England, from which she probably took her name Julian. As an Anchoress, she chose a solitary life of religious devotion, taking a vow of stability of place. She was permanently enclosed in a cell attached to a church, and through a window in the cell, she could offer spiritual counsel and guidance. Perhaps our best way to understand her life and role is to think of her as an “anchored presence” – an anchor - offering stability and hope by her presence, life of prayer and seclusion. Her “anchored presence” of seclusion ironically meant that she was more fully alive in this world through hiddenness and compassion.

And yet again, ironically, she literally fell out of sight for much of the 600 years since her lifetime, only in our generation of the past several decades to be found again, and speak so piercingly into our contemporary life, becoming in our day, one of the most read and popular mystics of the 14th century.

Thinking about Julian as an anchoress, an “anchored presence” - an anchor - asks of me to be as real as I possibly can, to be grounded in the stuff and circumstances of my life, and, instead of worrying whether a particular doctrine of the church is true, to ask myself the anchored question: “Am I true”? For at the heart of the word “question” is the beautiful word “quest”- a word which makes sense of years of endless probing and questioning that Julian underwent in search of the saving truth and hope for which she is so justly famous.

We know so little about her: was she a nun? Was she married? Did she have children? She called herself “unlettered”, but was she? What we can say - and it is almost entirely because of her Revelations or Showings of Divine Love – she was a woman of profound intellect: she is considered amongst the greatest of English theologians; she can be ranked with Chaucer as a pioneering genius of English prose. She wrote out of her experience, and what she writes is not academic or heady theology. She was a realist about the human condition; and she was an amazingly courageous and clear thinker. Remember she was a woman, and it was a time when heretics were burned at the stake.

As I reflect on Julian I am often reminded of that young Jewish woman, Etty Hillesum, who died in Auschwitz on November 30, 1943, and who kept an extraordinarily moving diary. As she lay on her plank bed she could hear the women and girls around her sobbing and crying and saying “I don’t want to think, I don’t want to feel”. It was then that she prayed “Let me be the thinking heart of these barracks”. Just as Thomas Merton called Julian a “wise heart”, so Etty’s cry to be a “thinking heart” reminds me of the importance of reason and being real, yet reason has its limitations, and with Pascal we need to see that “The heart has its reasons which reason doesn’t know about”.

Perhaps her most famous saying is: “All will be well, and all will be well, and every kind of thing will be well”. What is so astounding is that she could say these words in the very context I have described. These are words of hope, not optimism, not putting our faith in the outcome, but rather realising that whatever happens, things still make sense within the horizon of God’s larger story. In the face of so much that was wrong in the world and in the human condition, Julian could still say these words God had entrusted to her. Margaret Guenther, in a workshop I invited her to run in Adelaide, 20 years or so ago, talked about those words of God Julian makes so much of. She suggested we think of the women and children in cattle trucks on their way to Auschwitz to certain death. She pictured mothers holding their little children in their arms, and saying to them: “It's going to be alright. It’s going to be alright”. This is surely a truth that can only be forged in the furnace and crucible of love. For Julian, love is our Lord’s meaning: but it is also our meaning.

She also reminds us that we are a “marvellous mixture of both well-being and woe”, of good and bad. The emphasis is on both/and, and not on either/or. This is what Rowan Williams calls “double vision’– “the vision of [our] own fear and the vision of the love that overcomes it”. This “double vision” means that we face two realities: “un-reconciled pain and unexhausted compassion, the history of men and women and the history of God with us”. This double vision means that we have to learn to live with the tension of acknowledging that we live with the both/and. As Julian says: “Peace and love are always in us, living and working, but we are not always in peace and love”. Or as Michael Leunig suggests in his well-known prayer, there is only “love and fear”. We may choose to speak or act from either space because they are both within us.

Julian’s great gift to us is to help us see that both are true: “peace and love are always in us, living and working” – which she calls the higher or absolute truth – and “we are not always in peace and love” – which she calls the lower or relative truth. She goes on to say: “For we do not fall in the sight of God, and we do not stand in our own sight; and both these are true, as I see it, but the contemplating of our Lord God is the higher truth”. Living with this “double vision” means that while we don’t deny or ignore Julian’s lower truth, we are never to ignore the higher truth. Julian focussed completely and intimately on Jesus – on his passionate, compassionate loving – and this allowed her to see how real and close his identification with humanity really is, and also allowed her to stay with the contradiction, and not try to solve it. She was both honest and authentic. “We have in us our risen Lord Jesus Christ, and we have in us the wretchedness and harm of Adam’s falling … And so we remain in this mixture all the days of our life”. And yet, in spite of such pain, “he touches us most secretly” and “protects us so tenderly”. This is the God who does not stop loving us in our falling, but at the same time does not want us to fall into despair. This imaginative insight into the human condition radically transforms how I see myself, and it radically transforms how I see others.

One of Julian’s great admirers was Thomas Merton, who could say that “My fall into inconsistency was nothing but the revelation of who I am … I am thrown into contradiction: to realise it is mercy, to accept it is love, to help others do the same is compassion”. Contradictions are statements with elements that are logically at variance with one another, whereas paradox appears to be self-contradictory, but on further investigation may prove to be essentially true. If we can refuse to flee from the tensions that life brings us, we can discover the gift and transformative power that paradox carries, for life for all of us is always going to be a “mixture of well-being and woe”. The paradox which is our life contains both energy and promise, an astonishing secret at the heart of life, that is waiting to be discovered and lived. Michael Leunig says that the universal fact of being human is that we experience a crucifixion and a resurrection every day.

It is not surprising that Thomas Merton was drawn to Julian. He prayed to have a “wise heart” and realised the “rediscovery of Lady Julian of Norwich will help me”. He was impressed with the fact that she was “a true theologian with greater clarity, depth, and order than St Theresa: she really elaborates, theologically, the content of her revelations. She first experienced, then thought, and the thoughtful deepening of experience worked It back into her life, deeper and deeper, until her whole life as a recluse at Norwich was simply a matter of getting completely saturated in the light she had received all at once, in the ‘shewings’, when she thought she was about to die”.

Julian’s “wise heart” was able to discern what Merton calls “an eschatological secret”, at work already within everything that is. This secret “final answer to all the world’s anguish” has already been decided, and is a “great deed”, a deed of mercy and of life, already fully at work in the world and “ordained by Our Lord from the beginning”. And Merton continues: “This is, for her, the heart of theology: not solving the contradiction, but remaining in the midst of it, in peace, knowing that it is fully solved, but that the solution is secret, and will never be guessed until it is revealed”. This secret is the key to our life: it is nothing but a revolution in our consciousness, where we realise we are one with Him and in Him, and in fact, one with all that is. The contradictions remain, but they are no longer the problem. The mystery that paradox holds out for us is that we have the chance to touch perfection in imperfection, the sacred in the profane, and hope in despair. Julian’s great gift to us was her relentless questioning, and her courage to face the dreadful tension within. With her insights to help us, we can learn to live creatively beyond the surface form of contradiction or paradox, and discover the depth and richness at the heart of life, the “hidden wholeness”, the underlying unity of all things.

For Julian, God offers us liberation in all the places I least think to look, in brokenness, fear, disappointment, disillusion, limitation and death. To find light we go to the place of darkness; to find fulfilment and wholeness, we go to the place of emptiness and poverty; to find life, we go to the place of death. When Jesus said that the poor in spirit are blessed, he was saying that when we are poor in spirit we are in the right place. For it is here when we begin to experience the sufficiency of God’s grace. The tensions and contradictions of life that faced her and her fellow Christians became the focus for many years of wrestling and reflection.

As an Anchoress who had become gravely ill, she “conceived a great desire to receive three wounds in my life … the wound of contrition, the wound of compassion, and the wound of true longing”. It is precisely here, in the poverty of being wounded, that she experienced what the Australian poet Kevin Hart said: “I come to wound you and to heal the wound”. Or what Dennis Potter, the English journalist knew: “Religion is never the bandage, but always the wound”.

Her wound of contrition meant she wrestled for a long time over the mystery of sin. Sin has no substance, yet “it is the sharpest scourge with which any chosen soul can be struck”. She wondered why “sin was not prevented”, but she knew that “Sin is simply the way things are”. When sin abounds, grace abounds. We need to fall, and we need to see it: for if we did not fall, we should not know how feeble and how wretched we are in ourselves, nor, too, should we know so completely the wonderful love of our Creator”. “The reason we are oppressed by [our sins] is because of our ignorance of love”. Sin is necessary, and we need to recognise and accuse ourselves of sin, but not wallow in remorse either. God is not angry, and does not blame us, but looks at us with pity “for our failures do not prevent Him from loving us. In every soul which will be saved there is a godly will which never assents to sin and never will”. “Sin shall not be a shame to (us), but a glory”: healing is possible, when we offer our divided and contradictory self to God who sees our wounds “not as wounds but honours”.

The wound of compassion is the entrance into love, which alone makes sense of the brokenness of the Cross. Compassion asks us into places of hurt and confusion, challenges us to cry out with those in misery, mourn with those who grieve, and weep with those in tears. It is nothing less than full immersion into what it is to be human. As she gazes at Christ’s bloody head she tells us “Suddenly the Trinity filled my heart full of the greatest joy” (4). The crucial point lies in this identification of humanity in the person and sufferings of Christ, “knowing that God is not destroyed or divided by the intolerable contradictions of human suffering”. She could say: “some of us believe that God is almighty and may do everything, and that he is all wisdom and can do everything, but that he is all love and wishes to do everything, there we fail” (73).

Her third wound she asked for was the wound of longing which led her to trust that “Our natural will - the way we are made - is to have God, and the good will of God is to have us”. She realised that “…it is a very great pleasure to Him when a simple soul comes to Him nakedly, plainly and unpretentiously”. As a realist she accepted life as it is, and yet she was full of faithful trust. God did not say: “You will not be troubled” or “You will not have bitter labour” or “You will have no discomfort” but “You will not be overcome”.

She helps us see beyond a transactional God, and realise that in prayer we don’t have to try harder, but simply live with a God who is enough, whose grace is sufficient in whatever circumstances we find ourselves. She saw that “through our ignorance and inexperience in the ways of love we spend so much time on petition”. So she could say: “The best prayer is to rest in the goodness of God and to let that goodness reach right down to our lowest depth of need.” Her priority is the prayer itself, not its effectiveness in terms of tangible results. For “it is not our praying that is the cause of God’s goodness towards us … Our Lord is greatly cheered by our prayer. He looks for it and he wants it”. God’s goodness and God’s grace are enough! “The greatest deeds are already done”.

So, when we get in touch with the pain and anguish of our lives - be it the very personal pain of illness, our own or our friends, or the horrific pain and terror of war in Ukraine or Gaza - we need to remember just where God is in all this. The God of the Crucified One is simply there, at the heart of the terrible suffering, receiving the appalling impact of the disaster. Just as Bishop John Robinson, of Honest to God fame, when asked where God was when he was diagnosed with terminal cancer, could say that God was at the heart of that cancer, so Julian could pray: “God of your goodness, give me yourself, for You are enough for me. I can ask for nothing less that is completely to Your honour, and if I do ask anything less, I shall always be in want. Only in You do I have everything”. For Julian it is our ignorance of who we really are before God, and not our faults, that holds us back. Made in the image of God, we naturally reflect the relational, mutual community of the Trinity: we are most fully human when we realise our inherent capacity for self-transcendence, when we realise that unconditional love is our true nature.

I want to end with Julian’s most famous image, the image of the hazel nut. Julian writes:

“He showed me a little thing, the size of a hazelnut, in the palm of my hand, and it was as round as a ball. I looked at it with my mind’s eye and I thought, ‘What can this be?’ And answer came, ‘It is all that is made’. I marvelled that it could last, for I thought it might have crumbled to nothing, it was so small. And the answer came into my mind, ‘It lasts and ever shall because God loves it'. And all things have their being through the love of God”.

Alan Webster writes: “Julian’s most memorable image lives today in a new sense. It is the vision of the hazelnut; it is all that is made. For us this vision has been reinforced by the earth as observed by the astronauts returning from the moon, a tiny thing as small as a nut and yet the ground of all humanity. Julian’s conviction was that the earth, so microscopic against the cosmos, was held together because it was created by love, and that love was its meaning”.

Julian “desired many times to know what was our Lord’s meaning in the revelations she received”, but it was “fifteen years after and more, [that] I was answered in spiritual understanding. “Love was (indeed) his meaning”, which allowed her to experience the reality of God, and that “Love is our meaning”. Our contradictions are treasures, “treasure that we have in earthen vessels”, creative places, not waiting to be resolved but simply accepted and embraced as part of the profound and complex movement of growth that constitutes being human. Such contradictions that face us all, carry with them, in all their puzzling and seemingly impenetrable brick walls, opportunities for us to celebrate the transformative, renewing, freeing and hopeful power and promise of paradox. Julian’s understanding that “love was his meaning” came about because she was grasped by a vision and an experience of the Crucified Christ, enabling her to see our unity with Christ in his human suffering, and to centre her life on the human image of God and the divine image of humanity.

Philip Carter is a retired Anglican Priest. From 1988 he was the Adelaide Diocesan Advisor in Spirituality, and in 1997 he opened the Julian Centre, an independent, ecumenical spirituality centre in Mile End near the CBD of Adelaide. Throughout these years he offered spiritual direction, directed retreats and Quiet days of Reflection. Over the past two years he has published Journeying Towards Faith: Becoming What I Am and Ordinary Heaven: Exploring Spiritual Direction and the Journey of Human Life.

This is the text of the online talk he gave at The Well on Sunday 9 November. Click on the link to the talk here - and use this passcode to access the recording: rZ9To!G# https://us02web.zoom.us/rec/share/VacFvPzCwE1P1dc7EI-cjFeI-5h6Yfa7WsGrXOknirDaLvbl_DL97RtXfiOIiQ5K.6f_2UQTjF13n90rC?from=hub