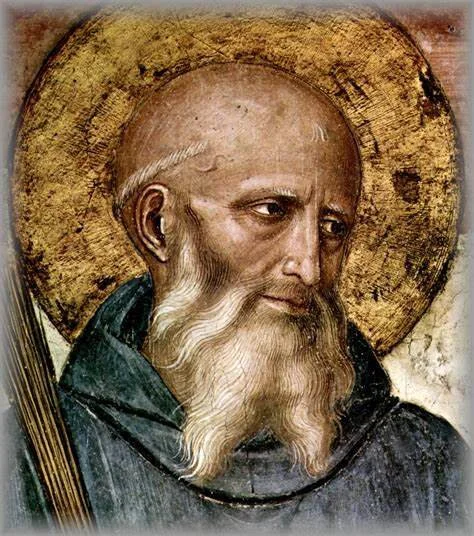

A depiction of St Benedict by Fra Angelico.

Born in the 5th century, Saint Benedict has had a profound impact on Western civilisation. His philosophy, outlined in his Rule of Life, is suffused with practical wisdom for daily living, and rests on a deep and meditative engagement with Scripture. As John Stewart* reflects, in the wake of Saint Benedict’s feast day on 11 July, the Rule has a powerful application which is just as relevant in the 21st century.

Saint Benedict has often been called the founder of Western monasticism and his impact on the development of religious life through the centuries has been profound. “The Benedictine way of life”, writes Joan Chittister, “is credited with having saved Christian Europe from the ravages of the Dark Ages. In an age bent again on its own destruction, the world could be well served by asking how simple a system could possibly have contributed so complex a thing as that.”[1]

Who was Saint Benedict? He was born to a distinguished and wealthy family in Nursia (today Nurcia), Tuscany, Italy in 480. During his studies in Rome he was disgusted by the moral squalor of his fellow students and he abandoned his studies in liberal arts and left Rome. He gave up his inheritance and went to Enfide, where he lived until he was 20. This is where he began his conversion to the monastic life, and where he became a hermit.

Groups of monks sought him out to be their leader, whilst at the same time there were a couple of attempts on his life because of his different outlook on monastic life. In 526 he transported his group of monks to Monte Cassino in the province of Campagna (which is midway between Rome and Naples), where he inaugurated the Abbey of Monte Cassino. It is considered to be the birthplace of the Benedictine order. In approximately 530, he wrote The Rule in low Latin.

His own personality is mirrored in his description of what kind of man an abbot should be: wise, discreet, flexible, learned in the law of God, but also a spiritual father to his community. Benedict was not a priest, nor did he intend to found a religious order. His main achievement was to write the Rule. He died in 547, aged 67, at Monte Cassino – near the altar where he received the Blessed Sacrament – while his monks held up his arms in prayer.

His enduring work is the Rule. There are two features of the Rule I want to reflect on in this brief article. The first is his approach to praying the Scripture, which is called sacred reading, or lectio divina. This monastic practice of prayerfully reading Scripture was first established in the 6th century by Saint Benedict and was then formalised as a four-step process by the Carthusian monk Guigo II during the 12th century.

The approach of lectio divina is the expectation that the Living God can be encountered in the living words of Scripture. When the text is approached prayerfully it is done so in the expectation that these are God’s words meant for here and now. The whole process is done in a spirit of lingering, mulling, savouring – allowing the words to sink down deep and waiting on God to move, to speak.

The four simple steps are:

Lectio. Take some time to quieten down. Read the passage slowly, attentively, gently listening to hear a word or phrase that is God’s word for you today.

Meditatio. Once you have found a word or phrase in the passage that speaks to you in a personal way, take it in and ‘ruminate’ on it. Gently repeat it to yourself, allowing it to interact with your thoughts, hopes, memories, desires.

Oratio. This is prayer understood as dialogue with God, a loving conversation with the One who has invited us into his presence. It is also consecration, prayer as the offering to God of parts of ourselves that we have not previously believed God wants. We allow our real selves to be touched and changed by the word of God.

Contemplatio. Maintain silence in order to catch any new insights. Simply rest in the presence of the One who has used his word as a means of inviting us to accept his transforming embrace. This is wordless, quiet rest in the presence of the One who loves us.

The second feature of the Rule I want to highlight is where Benedict describes the attitude or orientation we should have about ordinary daily life: stabilitas, conversatio morum and obedientia.

Stabilitas is being present to the here and now, rooted to the spot, resisting the urge to look to the next thing and the one after that. Being truly present to the moment, to the actual job in hand, to the people who are my companions now.

Conversatio morum translates as journeying on, being ready for change, ongoing transformation, being open to the new, the unexpected, the surprising. Being free to choose the life God is calling us to.

These two are in creative tension and need to be held in each hand together. Being present to the here and now, whilst also recognising that this isn’t the final word or destination. There is always more to be open to.

Obedientia comes from ob-audire, meaning listening very attentively. This is about listening deeply with the heart. It’s about deciding whose voice to listen to, whose to reject or avoid. This is the way to personal freedom. The Rule begins with the invitation to ‘listen with the ear of the heart’. This is about finding our spiritual truth, pathway, practice.

Being truly in the present moment, being open to where the Spirit is leading, and listening to deep inner wisdom – this is the heart of Benedictine life.

The impact of all this on my spirituality has been life-long and deeply helpful. It has urged me to live a balanced life where prayer, work and re-creation are in balance. It has helped me to pay attention to God’s engagement in all moments of my life – including the tough, painful and challenging times.

In her commentary on the Rule, Joan Chittister concludes:

Even at the end of his Rule, Benedict does not promise that we will be perfect for having lived it. What Benedict does promise is that we will be disposed to the will of God, attuned to the presence of God, committed to the search for God, and just beginning to understand the power of God in our lives ... The meaning of the human enterprise is for our taking if we will only follow this simple but profoundly life-altering way.[2]

This is an edited extract from Saint Benedict – The man who saved Europe from the dark ages, published in Heroes of the Faith – 55 men and women whose lives have proclaimed Christ and inspired the faith of others, edited by Roland Ashby. (Garratt Publishing, Melbourne 2015)

*The Rev’d John Stewart is a spiritual director, Co-Director of The Living Well Centre for Christian Spirituality, Melbourne, Australia (http://www.livingwellcentre.org.au/), and a retired Anglican priest.

References:

[1] From her introduction to her book The Rule of Benedict: A Spirituality for the 21st Century, (Spiritual Legacy Series, Crossroad Publishing, 2010)

[2] Joan Chittister, The Rule of Benedict: A Spirituality for the 21st Century, (Spiritual Legacy Series, Crossroad Publishing, 2010)